On AMUSEMENT and Natural Philosophy

If the Enlightenment keyword "attention" went hand-in-glove with the close observation required in the study of Natural History, the keywords "sport" and "amusement" aligned equally well with the experimental study of Natural Philosophy. Benjamin Vaughan recalled in his memorial statement how his wife Sarah especially excelled at engaging children in educational "sports" or amusements:

Mrs. Vaughan was particularly fond of children and loved to sport with them in a quiet way. She was desirous of instructing intelligent children, and would devote hours to teaching and telling stories to her children and grandchildren and others.

Juvenile Sports and Pastimes. To Which are Prefixed, Memoirs of the Author: Including a New Mode of Infant Education by Master Michel Angelo

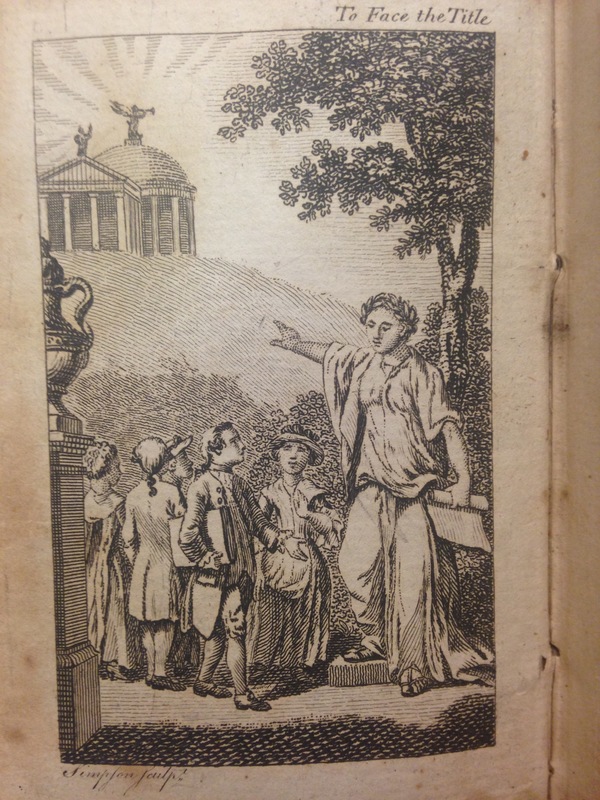

The author of this little volume claims that inspiration for the work came from seeing this engraving:

The meaning of it appears to me to be this: Minerva, who is supposed goddess of wisdom, is not to be courted by a too constant attention to study, and without devoting a small portion of time to amusement, for which purpose she is offering him a marble as an assistant to recreation.

"Useful" amusements include: the art of dump-making (i.e., making medallions), remarks on whipping tops and gigs, strictures on the game of trap-ball, making bows and arrows, and a "dissertation" on marbles.

Although the idea of learning through amusement and play has been traced back to the Renaissance (Shefrin, 2009), 17th century Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke (1632-1704) innovated by treating education, or the process of learning itself, as a science.

The Newtonian System of Philosophy Adapted to the Capacities of Young GENTLEMEN and LADIES. And Familiarized and Made Entertaining by Objects with which they are Intimately Acquainted

In this early edition of The Newtonian System, a child protagonist, Tom Telescope, entertains an audience of aristocratic adults and children--men and women--with a series of lectures on useful topics, such as gravity and the rotations of the planets, all in terms of everyday objects that could be found in the nursery.

James Secord (1985) has traced the emergence of The Newtonian System from its first edition in 1761 and claims that Newbery based his lectures closely on a treatise by John Locke, published posthumously as "Elements of Natural Philosophy." Locke had no apparent intention of publishing the treatise, which he had developed in 1690 to tutor the 12 year old son of his patrons, Sir Francis and Lady Masham.

In his An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, however, a copy of which is in the Vaughan collection, Locke advocates that all young gentlemen should be acquainted with science. Of course, it is important to remember that both Natural History and Natural Philosophy were at this time inextricably linked to the ultimate objective of understanding the wonders of God's creation, or, as Locke quotes on the title page of An Essay:

As thou knowest not what is the way of the spirit, nor how the bones do grow in the womb of her that is with child: even so thou knowest not the works of GOD, who maketh all things (Ecclesiastes, xi. 5).

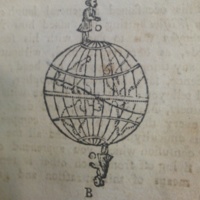

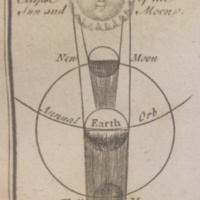

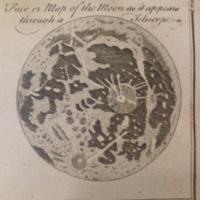

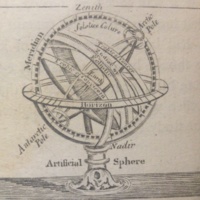

Engravings from The Newtonian System of Philosophy Adapted to the Capacities of Young Gentlemen and Ladies. And familiarized and made entertaining by Objects with which they are intimately acquainted.

In his Introduction to An Essay, however, Locke treats the concept of understanding with a metacognitive objectivity that we associate today more closely with scientific inquiry:

The understanding, like the eye, whilst it makes us see, and perceive all other things, takes no notice of itself: and it requires art and pains to set it at a distance, and make it its own object

The objective view of understanding, which, according to Locke, "sets man above the rest of sensible beings" is illustrated at left in Newbery's Newtonian System of Philosophy with the engraving of a child, first grasping the idea of its own reflection in the mirror.

In his treatise, Locke made the Scientific Revolution of Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, Descartes, and Newton accessible for the first time to a lay audience. But it was Newbery who distilled Locke's writing under the catchall name of a "Newtonian system." In the engravings below, he illustrates concepts of gravity and the movements of the planets.

The Amusing Instructor: or, Tales and Fables in Prose and Verse, for the Improvement of Youth with Useful and Pleasing Remarks on Different Branches of Science, 1777

Intriguingly, Newbery covers much of the same ground in The Amusing Instructor, even using the same graphics, but in this instance Natural Philosophy is preserved for conversations that Philander has with the boys. Conversations with the girls focus primarily on ethics and moral philosophy.

It is interesting to conjecture why Newbery chose to shift from Natural Philosophy as parlor entertainment for children and adults of both sexes to Natural Philosophy as a study exclusively for young gentlemen, although it may be that he was more closely following Locke's injunction that all "gentlemen" be acquainted with the science.

Letters in the Vaughan collection indicate that it was Benjamin Vaughan, who took the lead in teaching his children about Natural Philosophy and, like other gentlemen of his class, engaged in various forms of scientific experimentation at the Vaughan homestead.

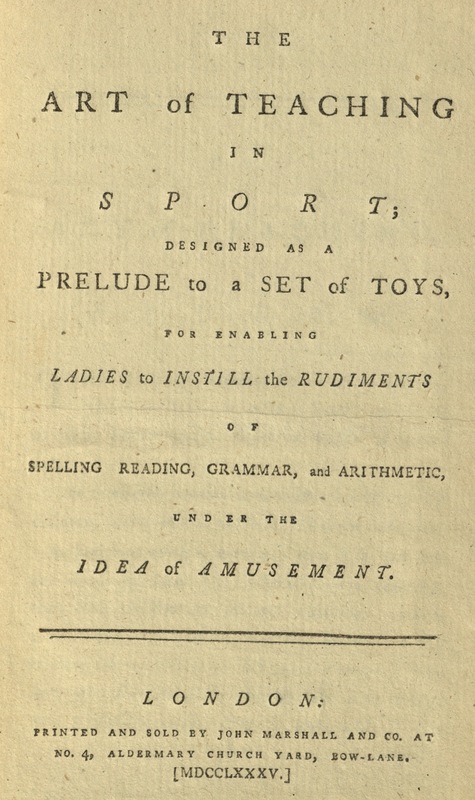

Sarah would have been responsible for their children's early basic training, which also relied on sports and amusements, like those described in The Art of Teaching in Sport.

The Art of Teaching in Sport; Designed as a Prelude to a Set of Toys, for enabling Ladies to instill the Rudiments of Spelling Reading, Grammar, and arithmetic under the idea of amusement.

The Art of Teaching in Sport presents a pedagogy that 21st century readers would readily recognize as learning manipulatives in the form of letters and numbers. To teach spelling, the author instructs the parent to provide the child with a "Spelling Box":

Let the infant have the spare box placed before him,--let him call it his own; as he acquires a knowledge of the letters let him deposit them in his box,--let him have them in his possession, and play with them when he likes,--allow him to shew them as his treasure, acquired by his industry and application. (original emphasis)

Although either parent might engage in this kind of active play with their young children, the emphasis in the Introduction is placed squarely on the mother's shoulders.

The sports of children, should afford exercise, either to body or mind; should contribute to their improvement, either in health or knowledge. The intelligent mother who walks abroad with her children, knows how to promote both at the same time. A judicious mother, conscious that it is not less her duty to form the disposition and capacity, than the constitution of her offspring, catches innumerable occasions of instilling benevolence, of infusing ideas, which are lost (irretrievably lost!) by her, who sends her little ones to take their airings with a nursery maid.

In conclusion, the author writes: "I view a mother as mistress of the revels among her little people; I say among, since she will find, that to engage, occasionally, in their plays, is the most effectual method of regulating their ideas and tempers."

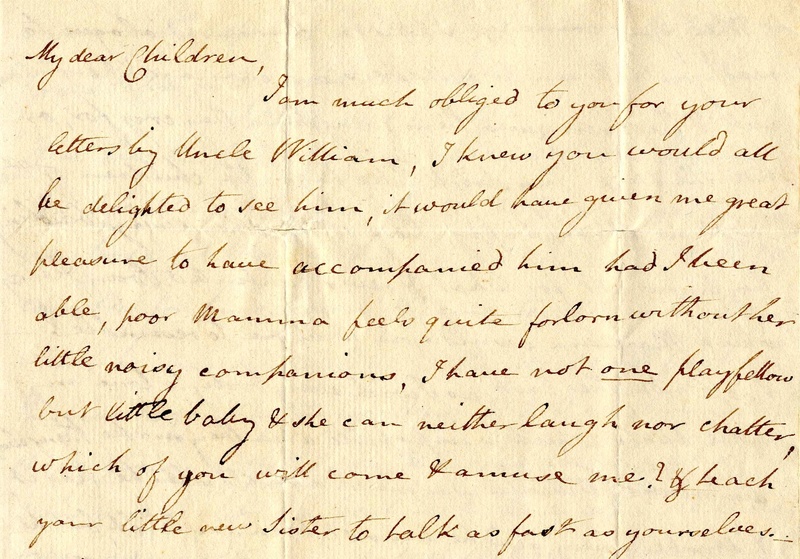

There is little question that Sarah took the injunction to be "mistress of the revels" of her children seriously, as the opening of her 1790 or 1793 letter makes clear:

...poor Mamma feels quite forlorn without her little noisy companions, I have not one playfellow but little baby & she can neither laugh nor chatter, which of you will come & amuse me? & teach your little new Sister to talk as fast as yourselves (emphasis original).

And later, when she closes her letter she adds:

I hope some of you will soon come to help the family concert, we shall scarcely have noise enough without you.

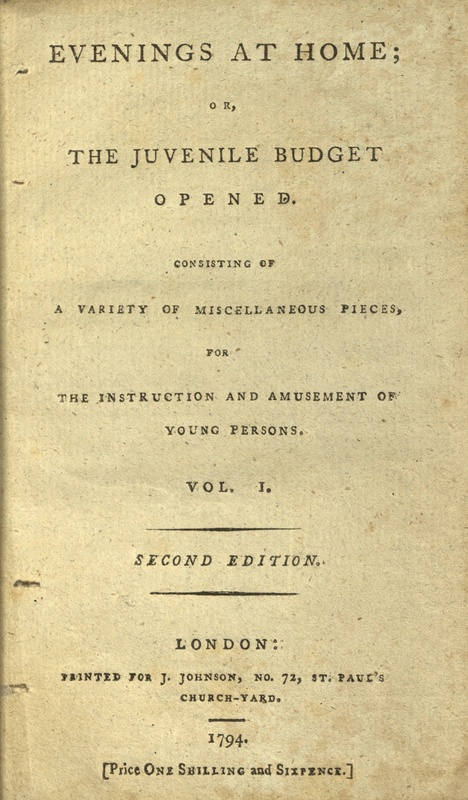

By family concert, Sarah may have literally meant music because she was an accomplished pianist, but it may also have referred to readings, dramatizations, games and conversation, as suggested in the Juvenile Budget Opened.

Evenings at Home; or, the Juvenile Budget Opened consisting of a Variety of Miscellaneous Pieces, for the Instruction and Amusement of Young Persons.

Like the toys, or manipulatives in The Art of Teaching in Sport, the Juvenile Budget Opened also involves an amusement that comes in a box, but the rules of the game are somewhat different. Sarah and Benjamin Vaughan were personally acquainted with authors Anna Laetitia Barbauld and her brother John Aikin, and it is tempting to imagine that the Vaughan household may have been somewhat modeled on the family at the center of the story:

The mansion-house of the pleasant village of Beachgrove was inhabited by the family of Fairborne, consisting of the master and mistress, and a numerous progeny of children of both sexes...The house was seldom unprovided with visitors, the intimate friends or relations of the owners, who were entertained with cheerfulness and hospitality, free from ceremony and parade. They...were ready to concur with Mr. and Mrs. Fairborne in any little domestic plan for varying their amusements, and particularly for promoting the instruction and entertainment of the younger part of the household. As some of them were accustomed to writing, they would frequently produce a fable, a story, or dialogue, adapted to the age and understanding of the young people.

The authors go on to explain the entertainment, which consisted of Mrs. Fairborne placing all the pieces of writing that visitors and relations had contributed into a box

...of which she kept the key. None of these were allowed to be taken out again till all the children were assembled in the holidays. It was then made one of the evening amusements of the family to rummage the budget, as their phrase was.

This meant that one of the younger children was allowed to pick a piece of writing that was then read by one of the older children and discussed by the family as a whole. In this period, when books and toys were scarce, families and friends often invented their own entertainments or copied excerpts and even entire volumes by hand.

****************************

Hand-Made Manipulative Games from the Vaughan Collection

In her letter to her children of 1790 or 1793, Sarah encloses stories copied for them by one of Benjamin Vaughan's favorite sisters Rebecca, or Aunt Becky.

Aunt Becky has been so good as to copy the enclosed nice stories, I think you are very happy children to have so many kind friends who take so much pleasure in improving & amusing you.

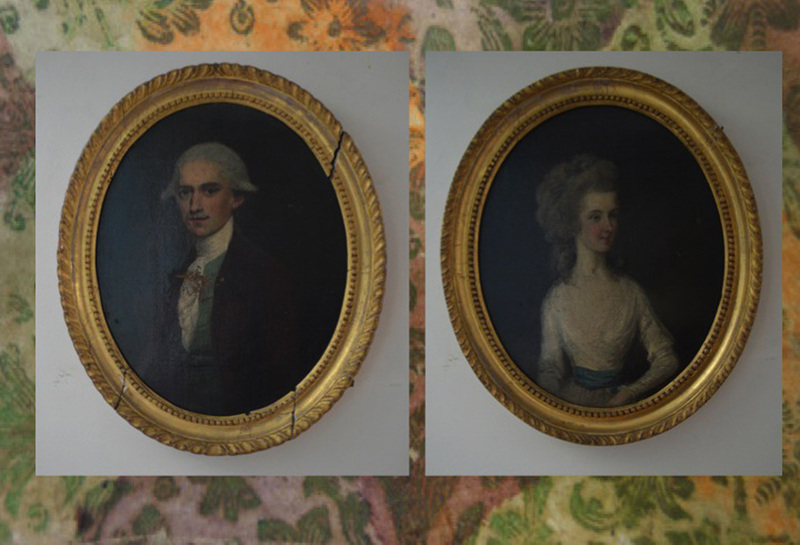

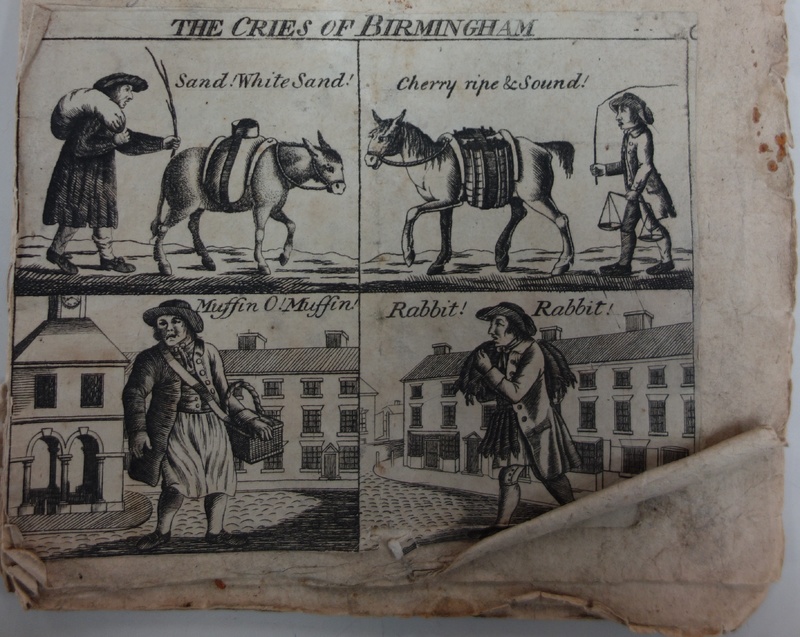

The conservation department at the American Philosophical Society retains many intriguing remnants of hand-made ephemera connected to the Vaughan collection that do not fit easily into the category of books. This hand-made manipulative is of particular interest because it is a play on the homonyms hare (rabbit) and hair (coiffure), and it has an added element of interest because Sarah's children have written in pencil under each of the engravings. The most elaborate image placed next to the rabbit is labeled "Mamma," which shows how Sarah's children were accustomed to having as much fun with her as she was with them!

The same piece of cardboard also features these more idealized beauties with big eyes and coiffured hair, who are each given a name in pencil of one of the children's many aunts. Number 1 in the upper left-hand corner is dubbed "Aunt Sally," and Number 2 to the upper right is "Aunt Barbara." Sally was very close to Sarah (whose nickname was also Sally), and was the aunt who eventually accompanied them on their first voyage to America.

Number 3 in the lower left is the "Aunt Becky," alluded to above. Aunt Becky later married the children's tutor, John Merrick, and moved to America to live next door to her brother's family in Hallowell.

Of course, it is unlikely that these engravings were modeled on the actual sisters. They are probably cutouts from fashionable magazines to go with the "hare" and "hair" word play established above. This shows that the children were used to personalizing their learning experiences in ways that Madame Barbauld certainly would have approved.

The assortment of learning manipulatives below--engravings with names of various birds to instill a knowledge of natural history and other games--include images that are in such bad shape they are not easy to identify. It is difficult to figure out exactly how the children played with these objects because the nature of this kind of hand-made ephemera leads to it being well-used, worn out, and eventually discarded.