Marriage to a Dissenter

Benjamin Vaughan (1751-1835) was born into a prominent family of Whigs and Unitarian Dissenters, who had sympathies for America during the Revolution. He attended Warrington Academy, a nonconformist institution for the children of Dissenters, and became a favorite student of the controversial Unitarian minister and natural philosopher Joseph Priestley.

It was through Priestley that Benjamin became private advisor to the second Earl of Shelburne (later, first Marquess of Lansdowne). As prime minister, the Earl of Shelburne sent Benjamin to France to play a significant role in facilitating the peace negotiations between England and the fledgling United States. Later, he helped Benjamin to a seat in parliament--a position usually denied Dissenters.

Benjamin's dissenting background meant that he was prohibited from attending public schools or graduating from any University in England. This freed him from the constraints of traditional elite education and made him more open to new ideas. It also placed him on an educational footing more compatible with his wife's, which had been conducted privately by the best tutors available.

An Episcopalian and Tory, Sarah Manning's father's religious and political views were diametrically opposed to Benjamin Vaughan's, but he agreed to the marriage on the condition that Benjamin pursued a practical profession and acquired a medical degree at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. Once this condition was met, Benjamin and Sarah were married on June 30, 1781.

When informing his close friend and mentor Benjamin Franklin of the event, Benjamin Vaughan wrote:

You gave me advice once about marriage, that amounted to mens sana in corpore sans (a healthy mind in a healthy body). The mens sana, as relating to the heart and head, I have found to a miracle and it very well makes amends for a tender frame. When a peculiar mind meets its fellow in all its caprices and pursuits, it appears to me that happiness is so far perfect; and I find it so in fact.

By “tender frame,” Benjamin was no doubt referring to Sarah’s petite size, in which they were also apparently well matched.

The “caprices and pursuits” almost certainly included their mutual love of learning and a united purpose to educate their children as enlightened and active citizens in a post-revolutionary world. The Vaughan collection at the American Philosophical Society library also includes a large portion of Benjamin's books and letters. When the Vaughan's moved to Hallowell in 1797, the Vaughan library rivaled that of Harvard University.

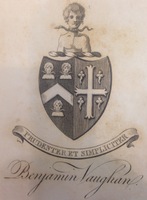

Like Sarah, Benjamin signed many of his own books by hand, but he also frequently pasted a printed seal with the Vaughan family crest and a more ornate signature on the inside of the cover.

Benjamin's family crest combines the crest of the Vaughan family on the left with that of the Manning family on the right. The Latin moto reads--Prudenter et Simpliciter (Prudence and Simplicity). The significance of boys with snakes wrapped around their necks is unknown.

****************************

The Vaughan Circle: Portraits in the APS Museum Collection

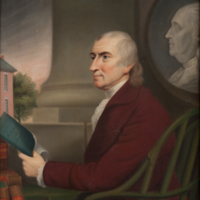

In 1750, successful merchant banker Samuel Vaughan (upper left) met and married Sarah Hallowell, the daughter of the King's Naval Commissioner in Boston. The couple moved to Jamaica, where Benjamin was born. They later returned to London, where they had a total of eleven children. Samuel was a founder of Warrington Academy, where Benjamin and his brother William attended, residing with their teacher, Unitarian minister Joseph Priestley (lower left).

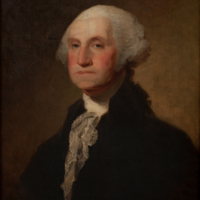

Samuel visited America several times and considered immigrating there, but his Bostonian wife preferred London. While in America, he became a member of the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia and contributed funds to build Philosophical Hall, which can be seen in the left-hand corner of his portrait. He acted as the Society’s first vice-president under cofounder Benjamin Franklin (upper right), also in bas-relief behind him. Samuel also befriended George Washington (lower right) and gave Washington an ornate marble mantelpiece, which, despite Washington's fears of appearing ostentatious, adorns his house at Mt. Vernon today.

When Benjamin Vaughan was 16 years old, he met Benjamin Franklin for the first time at the Vaughan family home in London. Although 45 years separated the two Benjamins, they became friends and correspondents for the remainder of Franklin's life. Vaughan idolized his mentor and convinced Franklin to allow him to compile and edit a volume of Franklin's writings titled Political, Miscellaneous, and Philosophical Pieces, which was published in London in 1779. Even in the midst of the American Revolution, Vaughan hoped to vindicate Franklin in the minds of British readers. In the Introduction, he wrote:

"Reader, whoever you are, and how much soever you think you hate him, know that this great man loves you enough to wish to do you good: His country's friend, but more of humankind."

In a memorial statement about his wife Sarah, Benjamin Vaughan observed: "She never saw Dr. Franklin, being unable to leave her family when the Dr. touched at South Hampton on his way from France to America. But had he been able to visit London, her house would have received him." Although Sarah never met Franklin, it was the close association of Franklin with the Vaughan family and their extensive involvement in the American Philosophical Society that accounts for why Vaughan descendents gave such a large part of Sarah and Benjamin Vaughan's manuscript and book collection to the APS library.

Sarah may not have met Franklin, but, as her husband recalled in his memorial statement: "Dr. Priestley and Mr. Price were most closely connected with her and the latter possessed a character in many respects like her own." It is tantalizing to imagine how Sarah's character was similar to that of Richard Price (1723-1791), who was a moral philosopher and mentor to such radical social reformers as Thomas Paine (1737-1809) and Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), whom the Vaughans also doubtless knew. It may be that Sarah shared Price's broadmindedness and willingness to associate with people of different ranks and religious affiliations. As her husband observed, "Among the less elevated ranks of society she was always greeted as being utterly devoid of pride and ostentation, and as being ready to join in the joys and sorrows of others."

Benjamin Vaughan was a favorite pupil of Joseph Priestley, who dedicated his third edition of Lectures on History and General Policy to him. Although Price and Priestley disagreed on particulars, they were both leading Rational Dissenters, who rejected church authority, arguing that individuals could gain their own insight into God's works through reason and scientific inquiry. Priestley's unorthodox religious and political views finally made it impossible for him to remain in England, and he immigrated to America in 1794. As we shall see, Benjamin Vaughan's association with Priestley and other so-called political radicals led him to be suspected of treason, and he secretly fled to France, also in 1794.