Reforming Motherhood

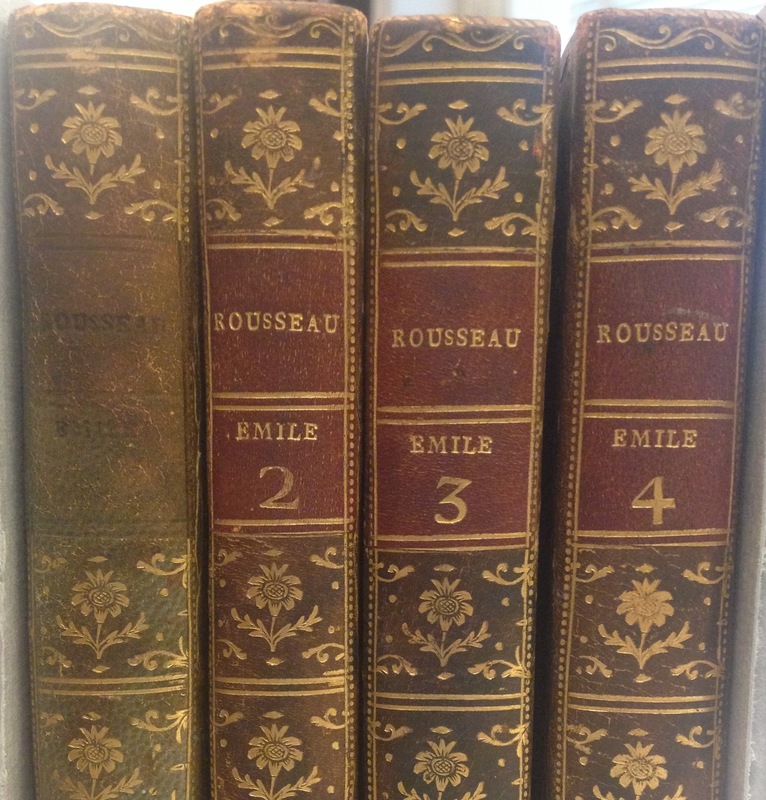

...when mothers deign to nurse their own children, then will be a reform in morals; natural feeling will revive in every heart; there will be no lack of citizens for the state.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile [Book I], 1762

Sarah’s facility with witty repartee was much more than just a refined accomplishment in this period. Conversation was viewed as one of the primary methods for men and women to improve their own minds, as well as those of their children.

Linda Kerber (1976) coined the term "Republican Motherhood" to describe the new role women played in the 18th century, educating their children to be the independent, active citizens required for a successful democratic republic. The ideology of Republican Motherhood is often traced back to John Locke's Two Treatises of Government (1689), where he argued "The first society was between man and wife, which gave beginning to that between parents and children."

18th-century children's authors and publishers took seriously Rousseau's injunction:

Address your treatises on education to the women, for not only are they able to watch over it more closely than men, not only is their influence always predominant in education, its success concerns them more nearly (Emile, Book I)

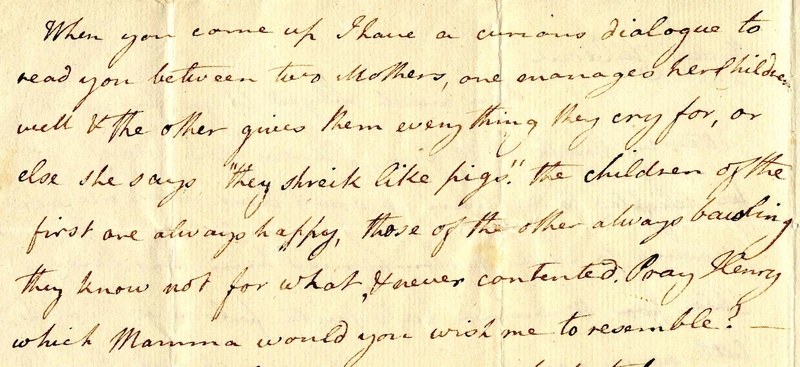

Many of Sarah Vaughan's books are written for or about mothers, illustrating the proper way to guide their children's behavior. In her letter to her children of 1790 or 1793, Sarah makes it clear that she believed these books played a vital role in her own and their "improvement" by providing models, not only of how to behave but also how not to behave. In simulated conversation with her children, she describes a "dialogue" she plans to share with them when next she sees them:

When you come up I have a curious dialogue to read you between two Mothers, one manages her children well & the other gives them everything they cry for, or else she says “they shriek like pigs.” The children of the first are always happy, those of the other always bawling they know not for what, & never contented. Pray Henry which Mamma would you wish me to resemble?

The letter continues:

I hope not the last, as I wish everybody to love my little dears which is impossible when they make themselves disagreeable, William was much diverted when he read it & says he is very glad he has not been so spoilt, but he thinks the silly Mamma deserves punishment & the poor children are much to be pitied.

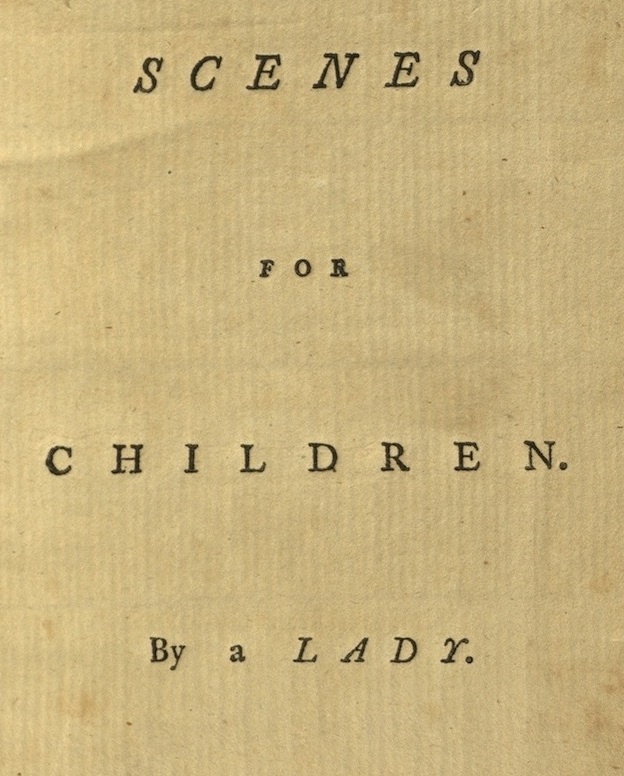

Although we cannot be sure which book in her collection Sarah is referencing in her letter, there is a book in the Vaughan collection that focuses on a series of dialogues about a good mother and a bad mother, titled Scenes for Children by a Lady.

Scenes for Children by a Lady

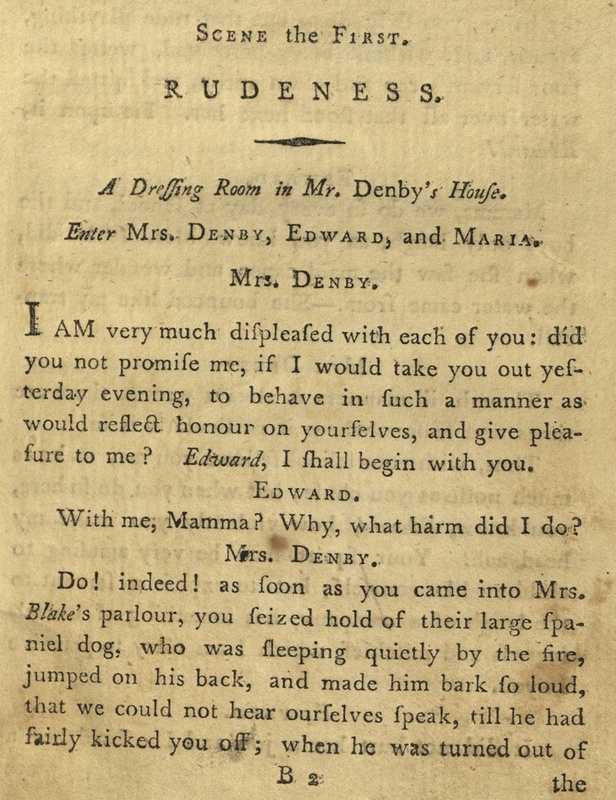

In the Introduction to Scene I, we are given a description of the main characters:

Mrs. Denby was one of the best mothers in the world; she was a widow lady of good fortune, left with two children, Edward and Maria, to whom she devoted her whole time.

The bad mother, with whom Mrs. Denby is contrasted, is a Mrs. Blake, who is described in the Introduction to Scene II:

Mr. and Mrs. Blake lived in town in a very grand stile; their house was magnificent, their equipage splendid, and their company fashionable...It is not to be supposed that so fine a lady as Mrs. Blake, would inspect the education of her children herself: it was quite enough to procure proper people to do it.

We are also not to suppose that just because Edward and Maria have a nearly perfect mother that they are themselves models of perfection. Edward is introduced, as "an open, noble-spirited boy, fond of a little mischief indeed, and very noisy and rude; but he never would persist in a fault." Maria is "generous and amiable; her capacity was surprisingly quick: but she would not easily own herself in the wrong."

During the Enlightenment, John Locke inspired a generation of parents and tutors to treat children as tabula rasa, or "blank slates," without the burden of original sin or "innate ideas" and thus capable of improvement with proper guidance:

Mrs. Denby had penetration to discover the faults of her beloved children; and it was the principal object of her attention to correct them. The tenderness, mixed with her reproofs, seldom failed of success: she opened their understandings, she appealed to their hearts, and they rectified their conduct themselves (emphasis added).

Readers enter Scene I, entitled "Rudeness," just in time to hear Mrs. Denby taking both her children to task for this particular fault: "I am very much displeased with each of you."

Enlightened parenting was not about indulging ones children's desires or boosting their confidence with praise. Rather, it involved paying close attention and correcting their faults in ways that would eventually make them active and independent thinkers suited to living in a successful republic.

Many of the authors who advocated for the role of mothers as the primary educators of their own children were women, notably the prominent poet Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743-1825). Barbauld's popular books for children were published in multiple editions in both Europe and America and translated into other languages.

Lessons for Children by Anna Laetitia Barbauld (née Aikin)

Benjamin Vaughan became acquainted with Anna Barbauld and her brother John Aikin (1747-1822) at Warrington Academy, where their father was an instructor. When Benjamin opted to stay an extra year at Warrington to continue his studies, he lived with the Aikin family. After marriage to Rochemont Barbauld (1749–1808), also a former pupil at Warrington, Anna Laetitia Barbauld went on to teach at Palgrave Academy--another non-conformist school for the children of Dissenters--where Benjamin's younger brother John Vaughan was later sent after Warrington closed. Sarah became a friend of Madame Barbauld and John Aikin after her marriage.

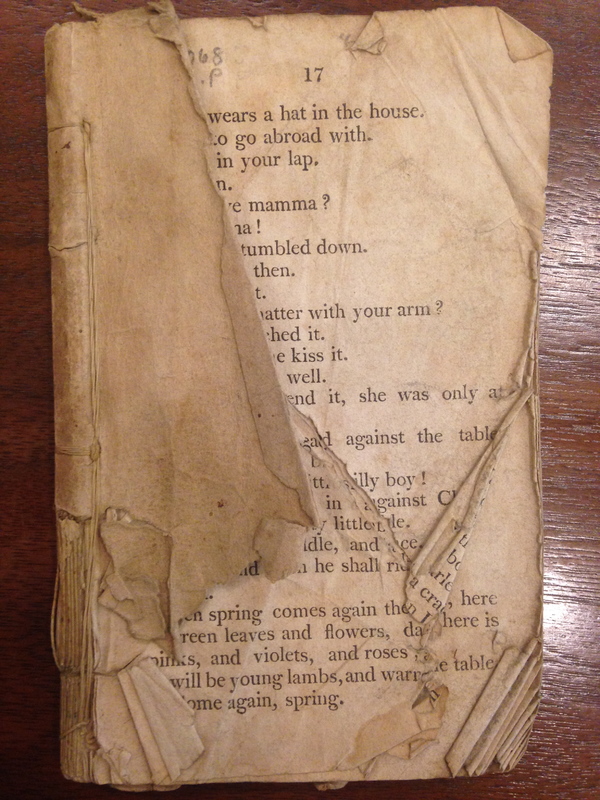

In this well-worn volume of Barbauld's Lessons for Children, we see the model of Republican maternal attentiveness, as a genteel mother follows her three-year old son, Charles, throughout his day, filling his ears with unceasing questions and artful conversation. Enlightened books for children in the late 18th century stressed the importance of rational inquiry into the workings of the actual world and avoided tales of fantasy or the supernatural.

Although later generations dismissed Barbauld's writing for children as didactic, during her lifetime, she was at the forefront of a shift in children's literature toward making accessible, even to the youngest children, such practical topics as Natural History, Natural Philosophy, trade, and manufacturing.

In the engravings illustrating her Lessons for Children above, we see three-year old Charles spending almost his entire day out-of-doors walking the grounds with his mother and discussing all manner of subjects from the importance of hard work and industry to the humane treatment of animals, including fish, and how to identify Autumn flowers: African marigolds, China-asters, and Michaelmas daisies. In the image on the left, we see Charles hard at work rolling the drive of their elegant country estate, while his mother says: "Where is your roller? Come roll the walk. Work well, and perhaps I may give you a halfpenny a day. Every body works but little babies; they cannot work."