The Role of Conversation

"Delightful talk! To rear the tender thought, To teach the young idea how to shoot, To pour the fresh instruction o’er the mind, To breathe th’ inspiring spirit, and to fix The generous purpose in the glowing breast." (Newbery, The Amusing Instructor, 1777)

"You will find Mrs. Vaughan really a mother who feels so much for the happiness of her children that her whole time is devoted to their improvement."

If it is true that Sarah devoted her time to her children’s improvement, how was this time actually spent? Doubtless, much of it, in conversation.

The role of conversation as a pedagogical method came to prominence during the Enlightenment, particularly in books designed for children, many of which were written as "familiar dialogues."

In this detail from one of Sarah's books, we see the ideal family portrayed sitting in the parlor and listening to the father reading. But passive listening was not modeled in these books. Children were expected to be curious and ask questions. Parents would then, through questions of their own, guide their children to rational answers. The family parlor was the training ground for enlightened inquiry, where the wonders of God's works were illuminated through Socratic dialogue.

At Warrington Academy, where Benjamin Vaughan and his brother William studied, innovative educator Joseph Priestley simulated "a virtual domestic unit" by organizing "group teas," where instruction was carried out through the art of conversation (Cohen, 109).

A Letter from Sarah Manning Vaughan

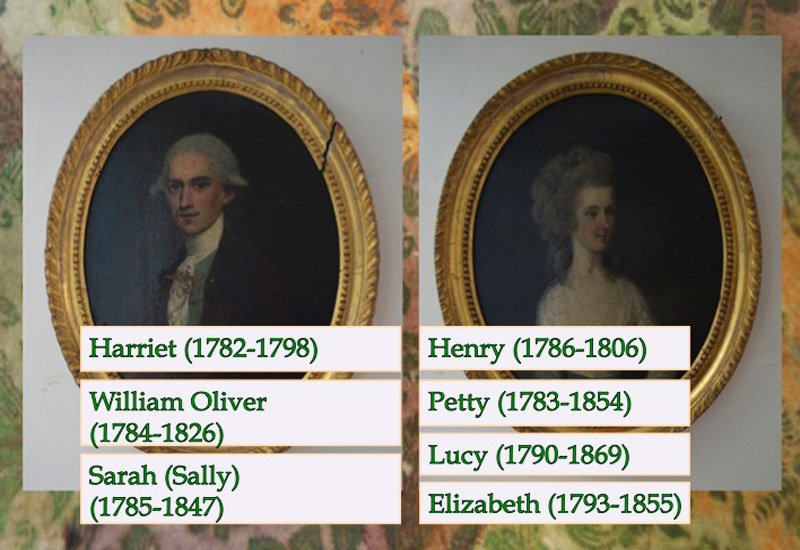

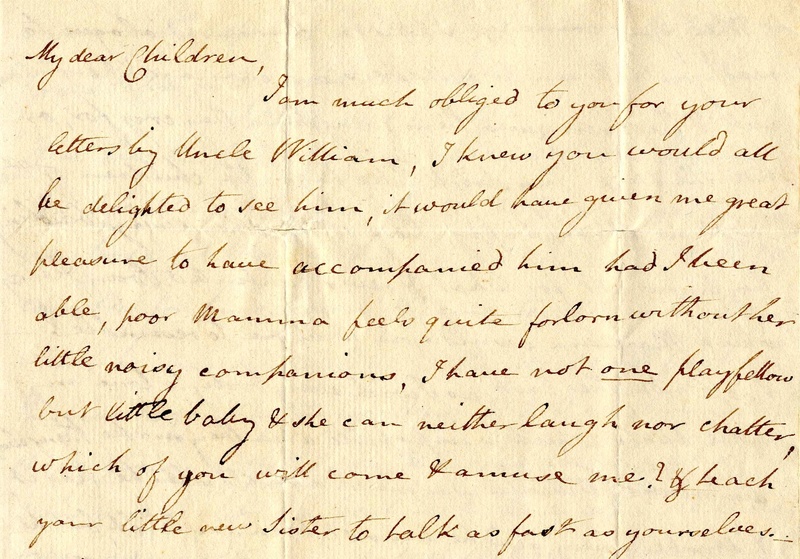

A rare glimpse of Sarah’s parenting style has been captured in a letter she wrote to her children during her confinement with one of her younger daughters.

I am much obliged to you for your letters by Uncle William, I knew you would be delighted to see him, it would have given me pleasure to have accompanied him had I been able, poor Mama feels quite forlorn without her little noisy companions, I have not one playfellow but little baby & she can neither laugh nor chatter, which of you will come and amuse me? & teach your little new sister to talk as fast as yourselves. (original emphasis)

Sarah continues her letter in a conversational style, capturing her children's interest and attention from the outset by connecting the story she is about to recount to their own immediate experience:

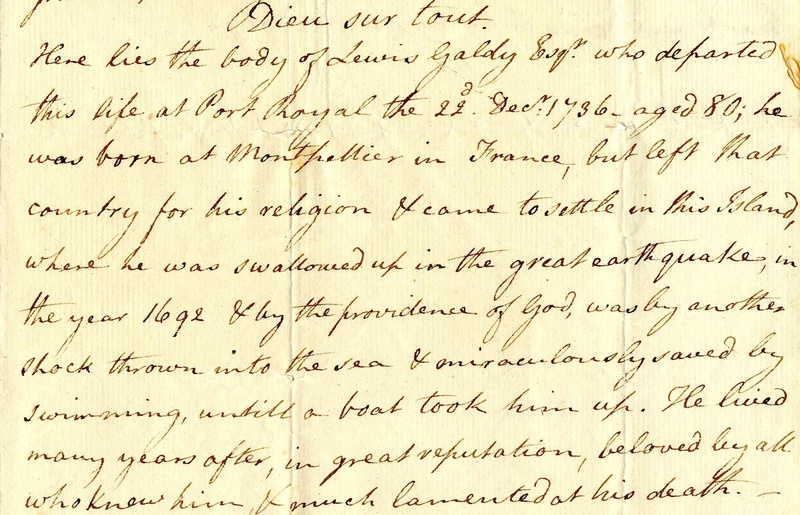

Mr. Edwards whom you saw at Southampton, has written a very amusing history of the West Indies...He mentions the following curious inscription on a tombstone at Green-bay, adjoining the Apostle’s battery, in Jamaica, perhaps your Grand Papa may have seen it.

Dieu sur tout.

Here lies the body of Lewis Galdy Esqr. Who departed this life at Port Royal the 22. Dec: 1736—aged 80; he was born at Montpellier in France, but left that country for his religion & came to settle in the Island, where he was swallowed up in the great earthquake, in the year 1692 & by the providence of God, was by another shock thrown into the sea & miraculously saved by swimming, until a boat took him up.

He lived many years after, in great reputation, beloved by all who knew him, & much lamented at his death.—

Again, simulating a conversation with her absent children, Sarah follows up with an observation and questions that can only be answered through the application of mathematical calculations based on a careful reading of the story:

It was very fortunate for Mr. Galdy that he had learnt to swim; pray how old was he, when he was swallowed up? & how long did he live after the accident?