The Pursuit of HAPPINESS

"You will find Mrs. Vaughan really a mother who feels so much for the happiness of her children that her whole time is devoted to their improvement."

Sarah Hallowell Vaughan to Mrs. Ridley, 29 July 1795

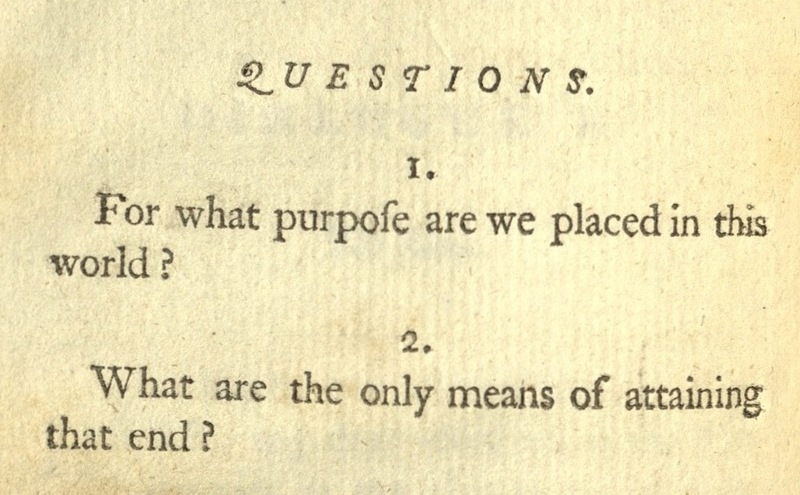

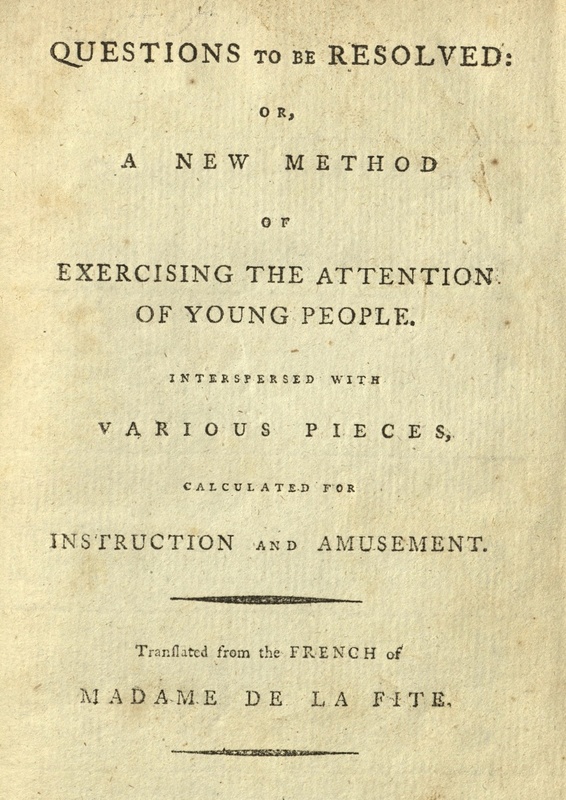

Questions to be Resolved, or A New Method of Exercising the Attention of Young People

Without question, one of the most persistent keywords of 18th century literature, especially for children, is "happiness." But what did Sarah Hallowell Vaughan mean when she said that Sarah and Benjamin's life's labour was for their children's happiness, and what did this have to do with their education or the move to America?

In Madame de la Fite's Questions to be Resolved, an idealized mother, Madame de Sainval, demonstrates what it means to "labour" for the happiness of ones children:

Madame de Sainval, the mother of Sophia and Paulina, presided over their education; and, whilst she employed the ablest masters to instruct them, she endeavored by her conversation to form their minds to virtue, and by practicing it herself to give them the most useful lessons...and being always careful to procure them such amusements as they might enjoy without disrupting their studies, and without acquiring a taste for frivolous objects, she with joy saw that nothing was wanting to complete the happiness of her children.

When Madame de Sainval moves with her daughters to the country estate of a bereaved friend, she invents an entertainment, consisting in a series of questions to which they must match the right answers. A question of primary importance is "For what purpose are we placed in this world?" The correct answer to which is: "To prepare us for becoming perfectly happy."

In ongoing dialogue with their mother and her friend Madame Belmont, Sophia and Paulina debate these and related questions. Several chapters are devoted to "What is the sentiment that produces the most happiness?" Paulina, the younger and more flighty daughter, overflows with possible answers from gaiety to compassion and from gratitude to generosity, but the thoughtful eldest daughter Sophia finally produces the answer: "The self-approbation which attends the habitual practice of virtue and piety, is the sentiment which produces the most happiness."

Madame de Sainval explains:

The true source of the purest pleasures, and that which renders most easy the fulfilling our duties, is contained in Sophia's answer. And this self-approbation, which attends the practice of virtue and piety, supposes likewise all the happy sentiments you (Paulina) have mentioned. (original emphasis)

In closing, she quotes "one of the most famous writers of our age":

Supreme happiness consists in inward contentment. It is in order to deserve and obtain this that we are placed here, and that, endowed with liberty, we are tempted by passion, and restrained by conscience. (Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile, Book I)

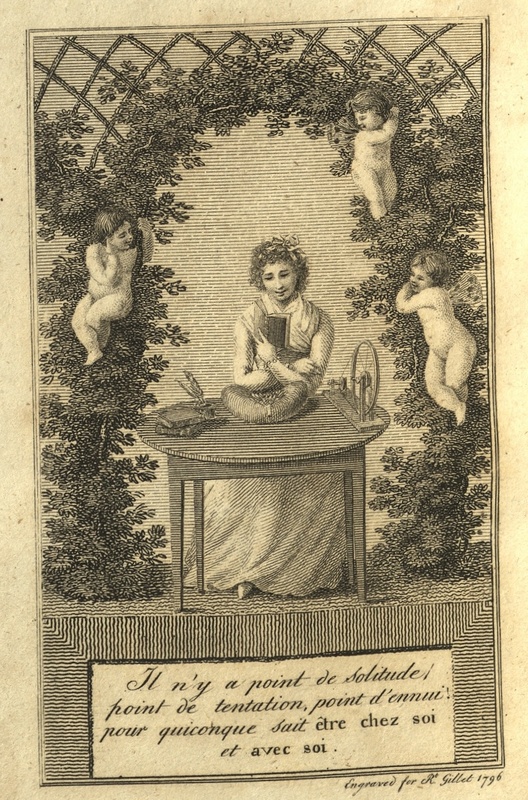

The Pleasures of Reason: Or, the Hundred Thoughts of a Sensible Young Lady.

Frontispiece from The Pleasures of Reason: Or, the Hundred Thoughts of a Sensible Young Lady. In English and French by R. Gillet, Lecturer on Philosophy, and F.F.R.S., Third Edition. 1798.

"Inward contentment" is illustrated in the frontispiece engraving for The Pleasures of Reason. The French phrase at bottom may be translated as: "There is no solitude, temptation, nor boredom, for those who know how to be at home with themselves."

In the preface, the author instructs the reader on the art of self-reflection, exhorting them to focus on the goal of happiness:

The imagination is not the only faculty you have to cultivate; your situation in life, and that which is to form your happiness, should constantly employ your thoughts, and consequently influence your conduct in your studies, your improvement, your pleasures, and even your misfortunes. What an art! what a talent! Do not imagine, my Young Readers that you are incapable of possessing it...

To reinforce the 100 sensible thoughts presented in the work, the author provides an allegorical map, depicting youth's journey across the "Ocean of Experience." At bottom left of the map, we see a matronly Minerva instructing her young charge how to navigate from "Dark Bay" through the "Rocks of Idleness and Obstinacy," passed the "Islands of Misery, Disappointment, and Dissipation," and around "Cape Grief," which lies just off the coast of the "Land of Remorse."

The path continues around the "Archipelago of Promises," eventually leading to the Satisfaction and Reward of "Success Island." But to arrive safely at the Terra Firma of Happiness and the Plains of Content, youth must first navigate the treacherous "Rocks and Whirlpools of Presumption," guided by the twin light-houses of Reason and Religion.

"The Terra Firma of Happiness" was the ultimate goal in this "Allegorical Map of the Tract of Youth to the Land of Knowledge," depicting a ship's journey across the "Ocean of Experience."

As fanciful as this might sound to 21st century ears, there is little doubt that it was a topic of gravity and even urgency in a time of high infant mortality. Through virtue, the Terra Firma of Happiness could be secured in this life but, more importantly, in the life hereafter. In the words of the idealized mother Mrs. Denby in Scenes for Children by a Lady when discussing with her children the sudden death of one of their friends:

You, my dear children will, I trust, be of this happy number, and redeemed from all misery, from all evil, re-join your little friend in those realms of purity and peace, where all tears are wiped away from all faces, and there is no pain, no sorrow, no death!

For Sarah Manning and Benjamin Vaughan such thoughts can never have been far away with their almost constant worry over the health of their eldest child Harriet.

Rounding "Cape Grief": the Death of Harriet Vaughan

It is not entirely clear what ailed Harriet Vaughan, but she was sickly from birth and required frequent excursions to the seaside for convalescence. Even this early portrait was most likely done with the idea that Harriet might not be long for this world. As the letters in the APS Vaughan family collection amply demonstrate, Harriet's health was the constant preoccupation, not only of her mother but also of her extended family. As Sarah Hallowell Vaughan wrote to Sarah in 1795:

"I shall not be free from anxiety till I hear of your safety and that my dearest little angel (Harriet) is safe and not suffered more than might be expected from the Voyage."

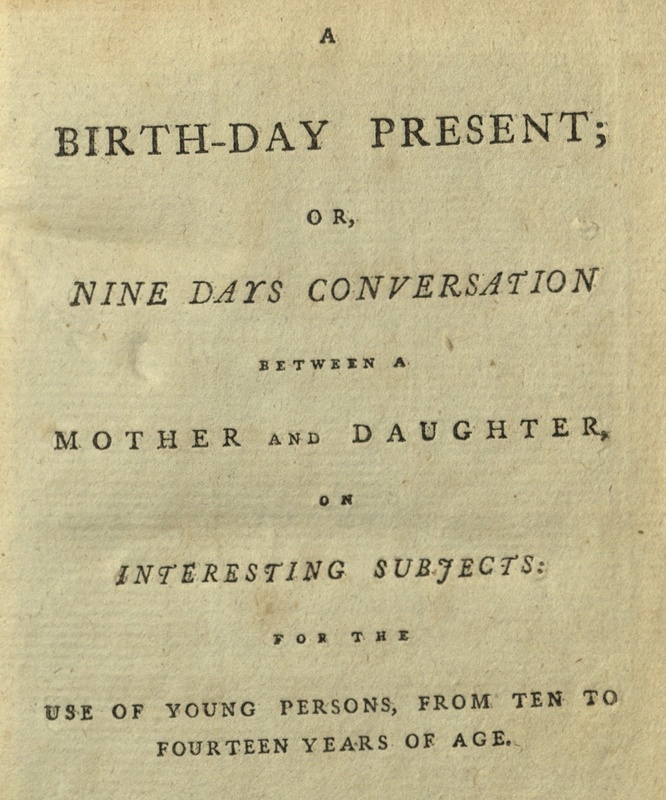

In the Vaughan collection of books at the APS, there are a few signed by H. M. Vaughan (Harriet), including this volume, entitled A Birthday Present, no doubt given to Harriet by her mother Sarah on her tenth birthday. It is particuarly moving to consider the hopes for Harriet's future suggested by the presentation of this volume.

A Birthday-Present; or, Nine Days Conversation between a Mother and Daughter

In A Birthday-Present, virtues are instilled through conversation over nine days, as follows:

Conversation Day One: Happiness

Conversation Day Two: Cheerfulness

Conversation Day Three: Good-Humour

Conversation Day Four: Benevolence

Conversation Day Five: Industry

Conversation Day Six: Moderation

Conversation Day Seven: Prudence

Conversation Day Eight: Religion

Conversation Day Nine: Advice Enforced

It is impossible to know whether Sarah actually had these conversations with Harriet between the ages of ten and fourteen. Harriet was thirteen when the family left for America, and it was hoped that the sea voyage might improve her health.

Apparently, it did, at least initially. Harriet was well enough when they arrived in New York to accompany the rest of the family to Little Cambridge (now Brighton) near Boston. She lived to be reunited with her father in 1797 when he finally joined them in America, but, by the time the family moved to Hallowell a year later, her condition had worsened, and she died the following winter.

In an epitaph for his eldest daughter, Benjamin Vaughan wrote:

Here be deposited the remains of Harriet Manning Vaughan, Daughter of Benjamin and Sarah Vaughan; who, having been wasted by a painful disease during nearly six years, died December 15, 1796; aged 16. Her zeal in fulfilling her duties, her love for the happiness of others, and her pious resignation, afford the hope that she will see that life, in which "the spirits of the just will be made perfect."

Letter from Sarah Manning Vaughan to Mrs. Charles Vaughan, 23 December, concerning Harriet's death on December 15, 1798.

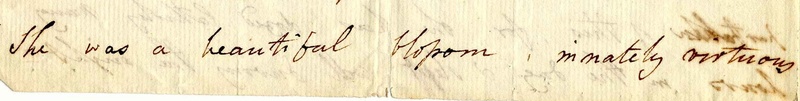

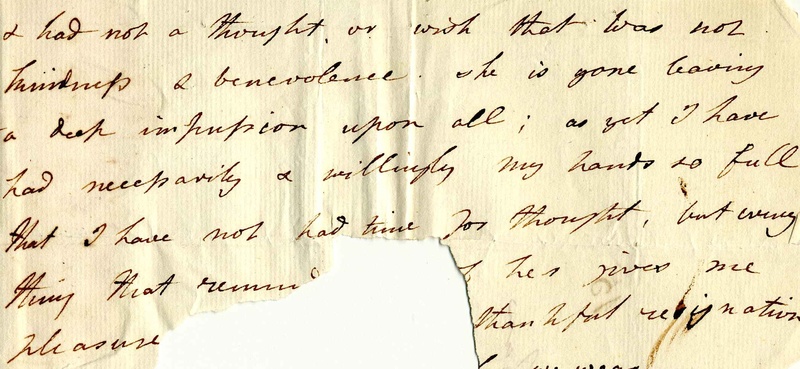

Harriet may have benefited from conversation, but letters from family and friends indicate that she may have been born with a naturally angelic disposition. In a letter to her sister-in-law, Mrs. Charles Vaughan, Sarah describes Harriet's death in detail:

...and had not a thought, or wish that was not kindness & benevolence. She is gone having a deep impression upon all; as yet I have had necessarily & willingly my hands so full that I have not had time for thought, but everything that reminds me of her gives me pleasure (torn section)...thankful resignation."

In closing her letter, Sarah makes an observation that is very revealing about the Republican lifestyle they had adopted since moving to rural Maine. She writes:

We all know your love for the dear departed too well to think it necessary for you to be at any expence on the occasion. It is the plan to avoid every thing that shall set an example of extravagance--adieu

Life in Hallowell

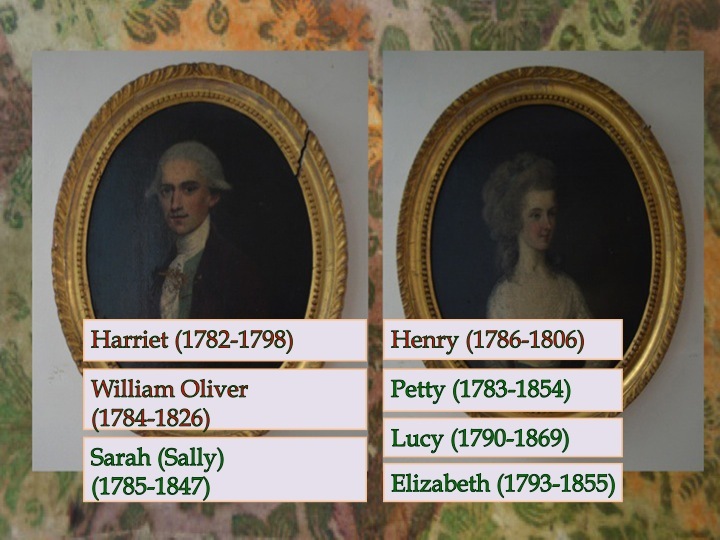

Names and dates of Sarah and Benjamin Vaughan's children. The fact that almost half of their children--marked in red--predeceased them, though tragic, was not uncommon in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

After moving to Hallowell in what was then Massachusetts, Benjamin and Sarah Vaughan devoted themselves to realizing their vision of an Enlightened republic, and it seems that their children responded favorably. In a letter to his mother dated 20 June 1800, Benjamin Vaughan wrote:

It has so happened that a farming life has fascinated all our children; and the more so, as they think they understand it. To tell them therefore of the charms of wealth and of London life has little influence with them. If their friends should think farming life to be servile, they would feel that a mercantile life was much more so...in the present unsettled state of affairs of the civilized world, and of their characters, it seems to me wise not to fix irrevocably upon a profession for any one of them, but so to educate them as that they may be able to adopt any of the more useful ones.

Indeed, changes were afoot that Benjamin and Sarah could not have foreseen. Their son Henry was tragically washed overboard on a sea voyage from the West Indies in 1806, and their eldest son, William Oliver, died at age 42, leaving his wife and three children in their care.

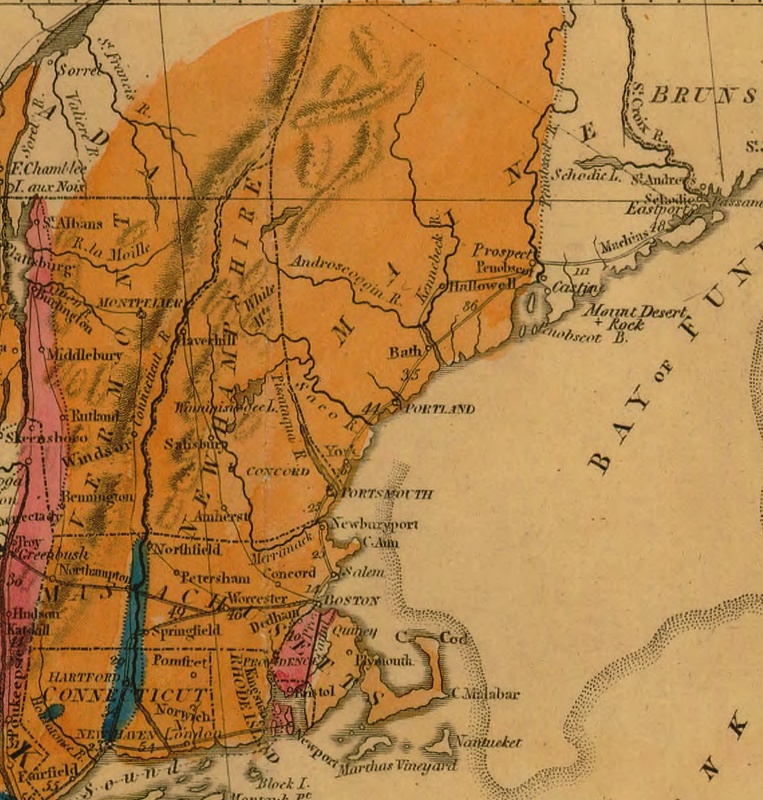

Detail from a map of the United States from 1818, around the time that Elizabeth Peabody traveled to Hallowell for the first time. The Kennebeck River and Hallowell are depicted toward the top, near the Canadian border.

Petty decided that a mercantile life was for him, and he moved back to England to live with his Uncle William, while their second daughter Sarah Junior (Sally) remained at home to care for her parents in their old age. John Merrick, who first accompanied Sarah Manning on her voyage to America in 1795, later married Benjamin's youngest sister Rebecca (Becky) and settled within walking distance of the Vaughan Homestead. The youngest daughters, Elizabeth and Lucy, also married and settled in the Hallowell community.

Sarah and Benjamin would no doubt have been surpised to read Louise Hall Tharp's 1950 biography of The Peabody Sister's of Salem, where she described their Kennebec home "as isolated and as self-sufficient as a medieval kingdom." Elizabeth Peabody (1804-1894), who later opened the first English-language kindergarten in the United States, spent time with the Vaughan family as tutor to the Vaughan's grandchildren.

But Tharp goes on to write about the Vaughans in terms that would have been more acceptable to their view of themselves:

The Vaughans were people of the world, but they were not worldly people. They had not the slightest touch of pretentiousness as they welcomed Miss Peabody, made her one of them and became her lifelong friends. They shared freely their knowledge, their ideals, and their experience, while Elizabeth's provincialism dropped from her (30).